Maltose Syrup from Scratch

A quintessential syrup for old school Chinese sweets (and some very off-topic chat on sugars)

Hi friends! This week’s post is slightly different — no cooking recipes here, instead, I will show you how to ferment your very own maltose syrup at home.

The process is not very complicated in terms of steps, but the science behind it is super cool, and I am also sharing some interesting notes on sugars that I have learnt during the process.

Why did I suddenly decide to make a syrup? Well, a couple weeks back I wanted to make some traditional sweets for CNY. While reading up various recipes, ‘Maltose Syrup’ (Mai Ya Tang 麦芽糖) kept appearing.

It brought feelings of nostalgia; my grandparents always had a jar in the kitchen. The syrup is incredibly viscous, but softens as it gets warm. I remember swirling bulbs of it out with a chopstick in summer afternoons, golden threads unravelling out of the jar as I lift my hand higher. Then I’d wrap it around the tip of the chopstick, and enjoy my very own ‘freshly-made’ lollipop.

Since moving to the UK, I have not seen it anywhere in Asian supermarkets. Nor have I seen it mentioned in any Western dessert recipes I have read.

Can I just make some from scratch? I thought.

Of course, given the power of Amazon, I could easily have ordered some online. But where would be the fun in that? And how else am I going to spend my time given it’s still lockdown? So I ordered wheat grains and sticky rice instead.

BUT FIRST, I had some other questions. What exactly is Maltose Syrup? What makes it different?

TL;DR — it provides extra viscosity/stickiness whilst lower sweetness compared to most other types of sugars/syrups. You can use it for glaze in sweet and savoury dishes alike (think char-siu pork or roast duck), but you probably want to do more research when using in baking in addition to reading my notes below.

Today, we will talk about some random info on sugar, the science and process of making the syrup at home, and then finally some thoughts on how to use in cooking.

OK, let’s lay the foundation with sugar compounds.

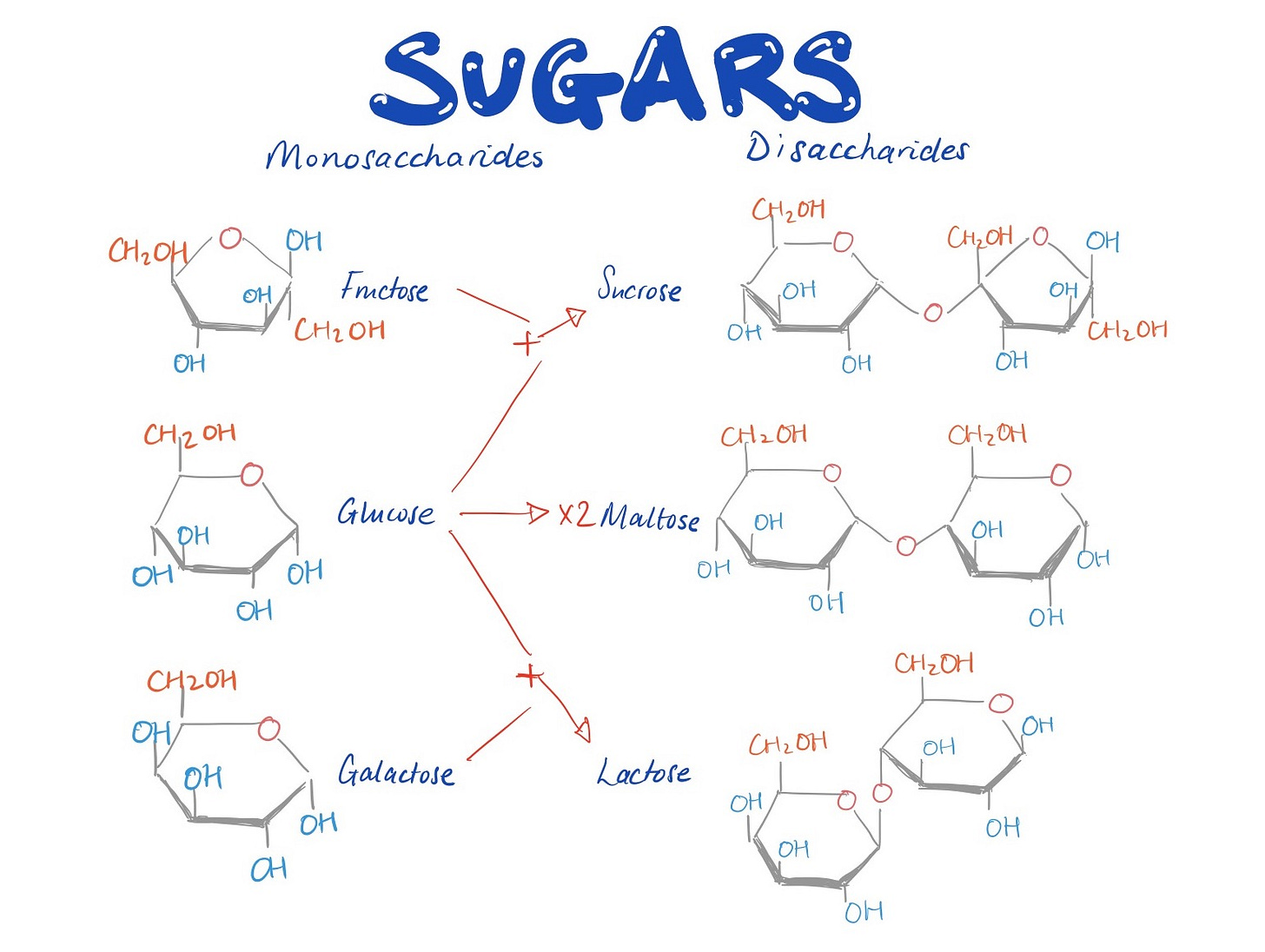

When we say sugars, they fall in 2 categories, monossacharides (aka simple sugars), and disaccharides (aka compound sugars, made up of 2 joined monossacharides). Longer saccharides are not usually considered as sugars.

We have all heard of the following compounds: fructose, glucose, sucrose, and lactose. Along with galactose and maltose, they are related as follows:

Most of these sugars are consumed by us in our daily diet, either through natural foods such as honey and fruits, or through sweeteners/syrups. I have summarised a table below of what sugars are present in some common ones.

Next, making the syrup and the science behind it.

The idea is simple: we start with more complex carbohydrates, and break them down into smaller sugar compounds by using enzymes.

This is actually the same process as making several other types of syrups. For specific types of syrups, we need to just find the correct carbohydrate and enzyme combo that will yield the desired end-product.

For making maltose, what we want is alpha-amalyse, which is abundant in grains post-germination. Thus, in my case: carbohydrate = glutinous rice; enzymes = sprouted grains.

Translating this into practical steps, we have the following:

Sprout some wheat or barley [see picture captions for how-to], and chop it up

Cook some glutinous rice, let it cool to around 60C (or slightly lower)

Stir chopped sprouts into cooked rice

Create environment for enzyme reaction and let it do its work (~40-60C)

Filter solids from resulting liquid

Reduce liquid to form syrup

Yes, simple.

Except sprouting grains in winter took absolutely A-G-E-S. Not to mention that you have to babysit your sprouts everyday to make sure they grow healthy.

But hey, lockdown, and therefore, time.

Scroll down for pics and breakdown of the process :)

Sprouting Wheat/Barley (both would work)

Creating that Enzyme + Starch Reaction

Reducing Your Syrup - just boil it for a bit, it took me around 1hr20m

Back to the science behind it. This process is similar to how corn syrup, barley malt, brown rice syrup, and the Japanese mizuame are made. Except you just replace the starch and sprouts with desired variants to achieve slightly different flavour profiles and compound mixtures.

Theoretically, you can also convert between the sugar compounds by using different enzymes because they are so closely connected (remember the first diagram?)! In fact, the various corn syrups (high-fructose, high-maltose) are made this way from your average corn syrup.

So how can you use maltose syrup?

In my opinion, you can use maltose syrup for any Chinese savoury dishes that requires a glossy glazing, especially meat, like char-siu pork. More commonly, it is used in making sweets, such as peanut brittles 花生酥, crunchy rice candy 米花糖, and sticky candy 牛皮糖. However, most recipes for both categories will not mention maltose syrup because other sweeteners (e.g. honey) are more readily available and recipes have adapted to the generic consumer, but there is no reason why you can’t substitute backwards by reintroducing it.

If you want to try it out by substituting into Western recipes, here are some reference data on relative sweetness, caramelisation temperatures, and water solubility.

Another thing to note is that maltose syrup made in this way differs from pure chemical versions because it retains some of the more complex compounds produced in the process — think date syrup/honey/maple syrup. As such, it has its own special flavour too: malty and delicate, a bit like barley malt crossed with brown rice syrup but less sweet.

Finally, as mentioned earlier, it is extra sticky and viscous, but could be warmed up for easier handling.

How much of the ingredients do you use?

Please will you use this same procedure when using ripe plantain at starch?