Yuanxiao, Tangyuan, and the Lantern Festival

Sweet glutinous rice dumplings but not as you know it (just in time for the festival this Friday)

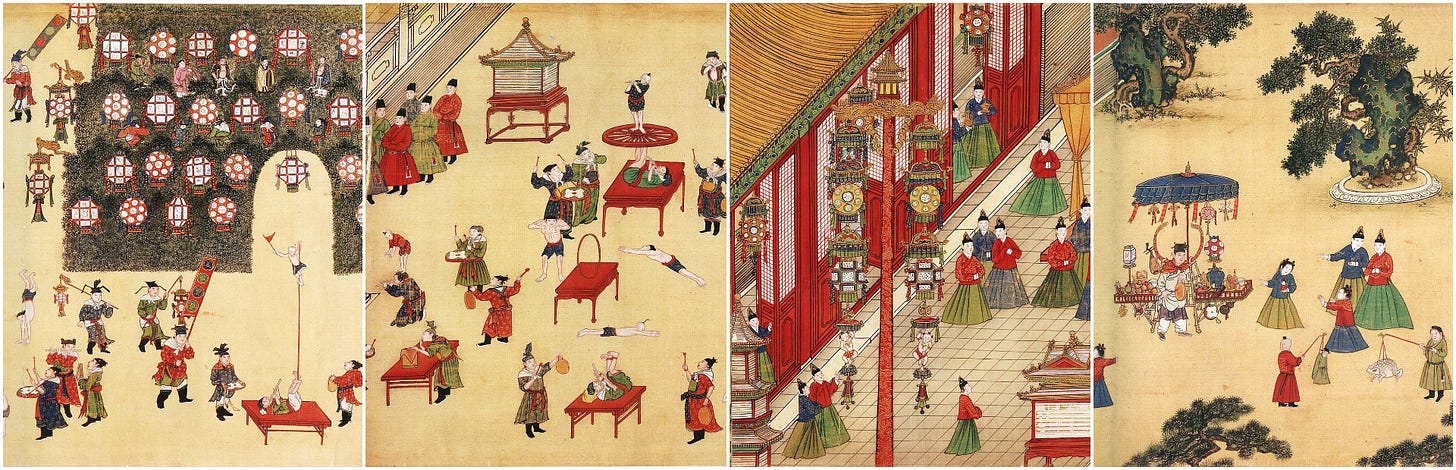

Growing up, the Lantern Festival (or Yuan Xiao Jie 元宵节 in Chinese), is one of my favourite traditional celebrations. Taking place on the fifteenth day of the Lunar year, it commemorates the first full moon of the year, marking the beginning of a new spring.

It is difficult to pin down the origin of the festival; it developed over time with influences from traditional Chinese beliefs, with influences from Buddhism and Taoism, steered by political motivations by emperors throughout history. Today, it is commonly regarded as the closing celebration of Chinese New Year festivities and a toast to family togetherness.

Whether historically or in modern times, the bulk of the celebration happens in the evening as the festival places great emphasis on the moon.

Numerous colourful lanterns would be lit up, particularly in busy night markets. People would walk around the town, often with families or friends, admiring fire displays and searching for their favourite lantern. ‘Light puzzles’ are a common feature too: long strips of paper hanging from the paper lanterns, brain teasers written on them, and the first person to guess the answer would win the lantern. Depending on the specific region, other activities includes Chinese acrobatics 杂技, firecrackers 爆竹, fire dragon dance 舞火龙, and crossing bridges 走桥.

Regardless of the region, however, glutinous rice dumplings are eaten as a part of the festival. Again, it is difficult to trace the historic origin of these dumplings, but one argument is that its appearance resembles the full moon. Today, we eat it as a symbol of reunion.

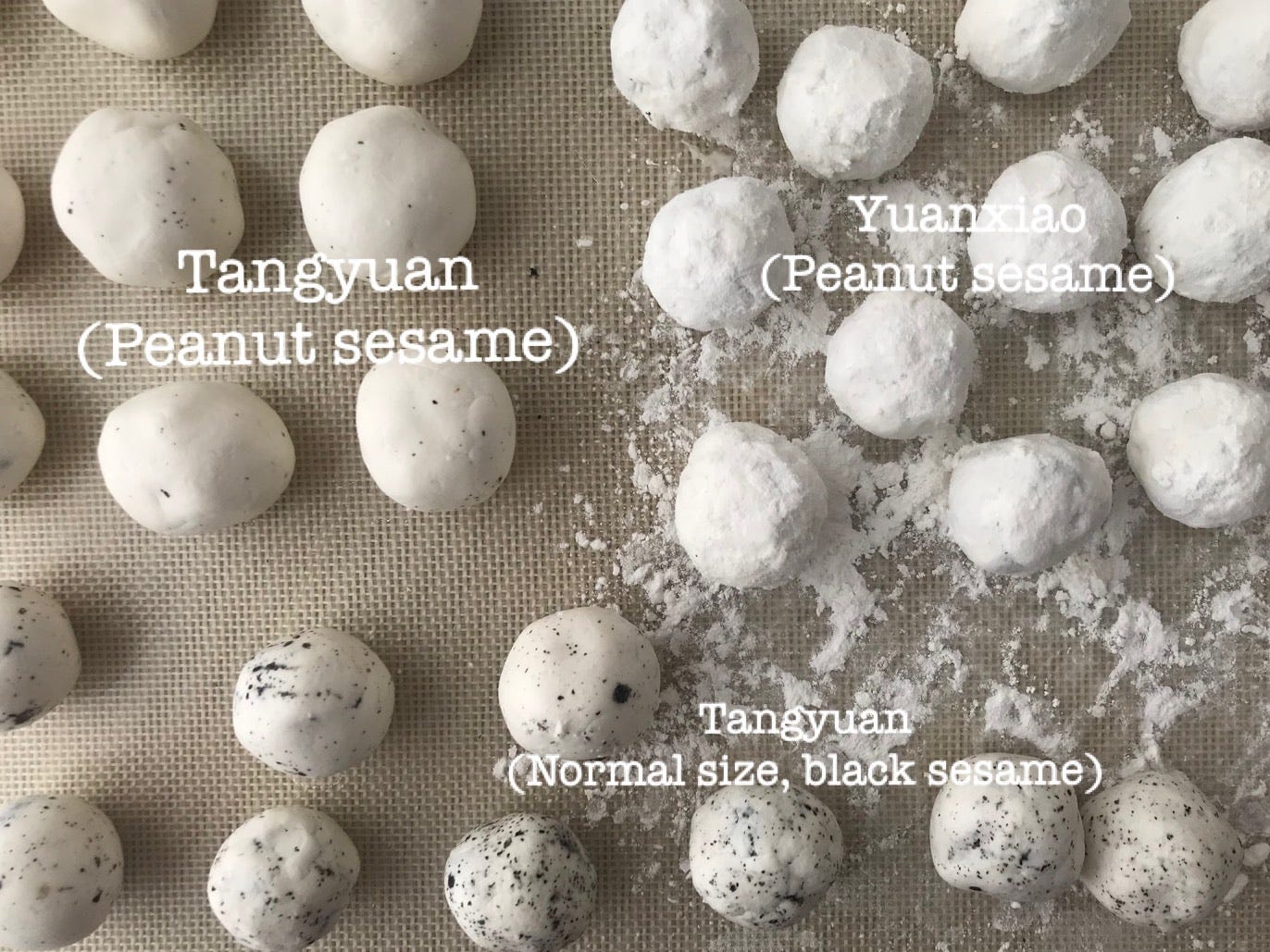

OK, you might think that you are familiar with glutinous rice dumplings — you can get ready-made frozen ones from almost every oriental supermarket. In reality, there are two versions: Yuanxiao 元宵 and Tangyuan 汤圆.

The ingredients of the two are exactly the same; the common type found in supermarkets is the latter, but some of you might have noticed the first bears the names of the actual festival.

You might wonder, therefore, what is the difference? The answer comes in three parts: region, method, and the filling.

In this post, I will cover how to make the lesser known yuanxiao while covering their differences with the tangyuan, and provide some brief notes for making the latter in the appendix. Both have a variety of fillings, but for now we will focus on the classic flavours: peanuts and black sesame.

Let’s get started.

The Filling

INGREDIENTS

From experience, the fillings of the two differ mainly in flavour and texture. Most of the time, the tangyuan tends to have a more singular flavour profile; the most common being plain sesame or plain peanut. In contrast, the classic yuanxiao combines the two, with walnuts sometimes added for extra depth of flavour. In the wider context, tangyuans can also have various savoury fillings, whereas yuanxiaos are exclusively sweet.

In terms of texture, yuanxiao fillings are usually ground more coarsely, varying between the larger peanut chunks and smaller sesame sprinkles. Tangyuan fillings are grinded finer, leading to a smoother, more oozy texture.

To understand a bit more their differences, I did a survey of various classic peanut/sesame filling recipes which you can find below.

The fillings are exceedingly minimalistic, consisting of nuts/seeds, lard, and sugar:

Nuts/seeds: The flavour base of the dumplings. On average, the ratio of this is higher in yuanxiao. Feel free to experiment with different nut combos, but note you will need blanched nuts for all nut varieties.

Lard: Lard is basically the Asian butter. In this context, the lard is what makes the filling more ‘oozy’, and you can see the ratio of lard is higher in tangyuan than in yuanxiao. Later on, you will see that it will help in shaping the dumplings. You can substitute with butter or shortening.

Sugar: Caster or icing sugar are most common, but I don’t think the type matters here. I added some honey in mine for more depth in flavour and it also helps to bind the fillings together. The amount of sugar is higher for tangyuan, and this does matter to offset the taste of fat due to their higher lard ratio. Ultimately, the sugar amount here can be adjusted according to personal taste.

I was also quite specific on how I wanted my yuanxiao to taste, namely:

as nutty as possible

good balance between sesame and peanuts

noticeably sweet but with a good amount of saltiness

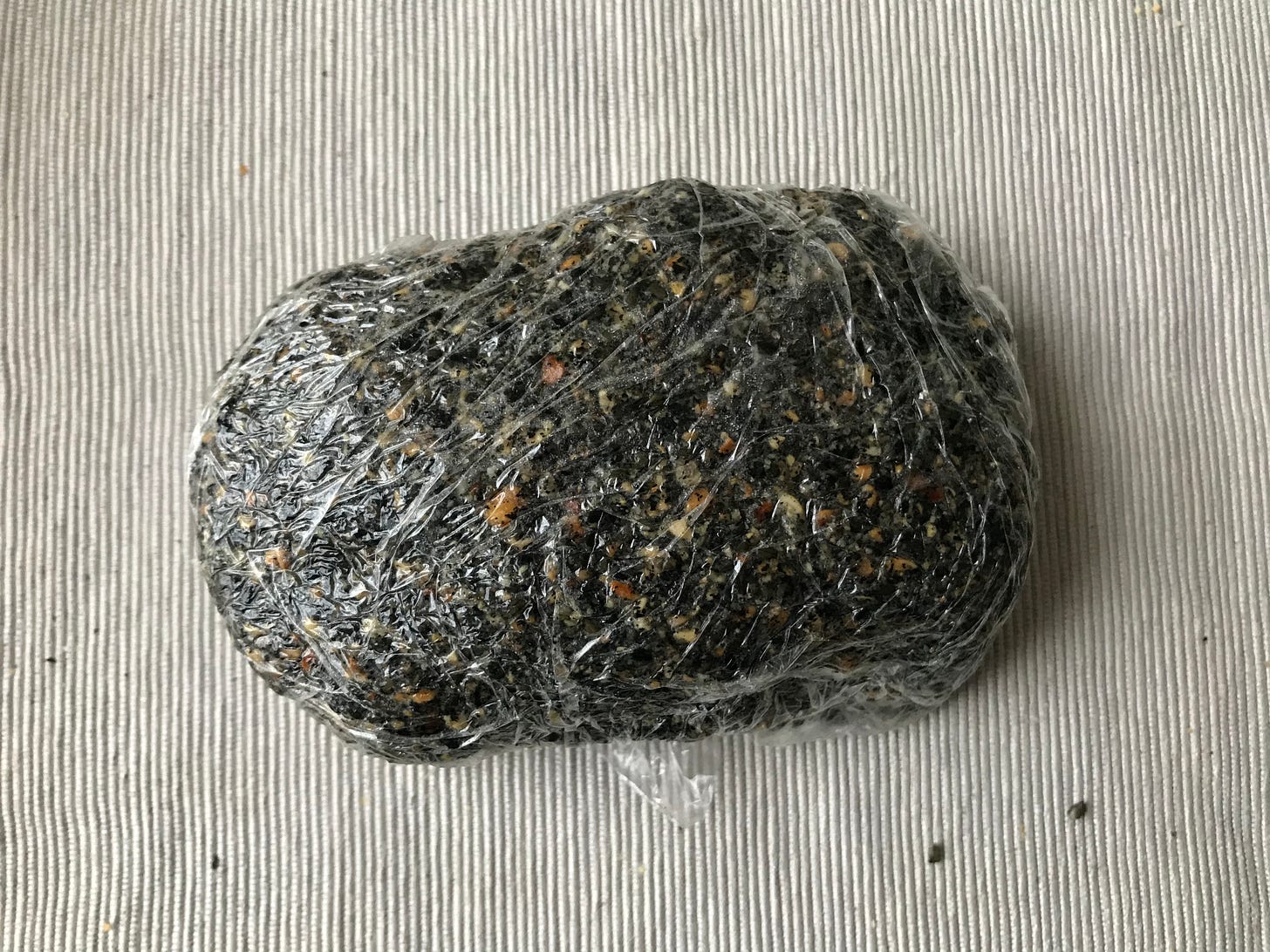

This meant lower lard, higher peanut-to-sesame ratio, and lower sugar. I skipped the walnut because they usually come with skin, which are hard to remove and gives a bitter aftertaste. After experimenting, the recipe I am happy with is the following:

85g toasted peeled peanuts

50g toasted black sesame

40g lard - melted

25g caster sugar

a generous drizzle of honey (~10g)

a good pinch of salt (1 tsp)

(I also made plain black sesame tangyuan for comparison, with the filling recipe in the table above.)

PRACTICAL TIPS

Making the actual filling is simple:

toast the nuts/seeds separately — I do it on the stove but it can be done in the oven

grind the nuts/seeds — by hand*

mix the drys (nuts, seeds, sugar, salt)

pour in the wets (melted lard + honey)

combine, wrap, and chill*

But there are some tips which might help you at each stage, and the process images and captions below should be useful.

*I recommend by hand as we want a coarse filling here. If you are making tangyuan filling, however, you will need a finer paste, so it is best to use a machine. Nicola Lamb’s post here covers how to make sesame paste at home very thoroughly. I would suggest aiming for a 5-10 minute blend judging by the 5-25-40minute process photos.

*In addition, you don’t technically have to chill the filling for tangyuan, although it is done nowadays because it will be easier to assemble. You also don’t have to chill it as long because it has a higher lard ratio. This difference between fillings treatment stems from the regional difference between the two, ‘South Tangyuan, North Yuanxiao’, alluding to the fact that yuanxiao is eaten mostly in northern China, where it is cold enough to keep the filling chilled (since street vendors would sell them freshly made outdoors).

Dough - N/A

Where is the dough section? Ah, this is the key difference between tangyuan and yuanxiao: there is no dough for the latter.

In Chinese, we say ‘roll yuanxiao, wrap tangyuan’, referring to the difference in their methodology, with yuanxiao being made by rolling balls of filling repeatedly in flour.

For tangyuan though, you will need a dough, see appendix.

Assembly and Storage

So, when your filling has chilled enough, divide and shape them into walnut-size balls. They don’t have to be perfect for either type of dumplings.

To make yuanxiao, you will need 1 large bowl, half-filled with glutinous rice flour (I use Foo Lung Ching Kee), and 1 bowl of water. Then, repeat the following:

toss balls in flour

dip in water

The latter has to be quick — you want to add a layer of moisture to the surface of the balls without washing off too much glutinous rice flour. By repeating this, the layers of dough-water will build up and form a film around your filling balls. It’s best to start with a modest amount of flour in bowl with constant top-ups to avoid too much flour getting wet in the process.

The number of times you do this really depends on how thick you want the glutinous rice skins to be. I went for 7 personally, but if you want more ‘mochi’ texture to your dumplings, you can roll them for more rounds.

In comparison, to make tangyuan, you would now take your glutinous rice dough, divide into small wrappers, and encase the filling inside. See appendix for notes.

The resulting various glutinous rice balls pre-cooking:

At this stage, you can decide whether you want to eat them straight or freeze them. THE CATCH, however, is that yuanxiao does not store well — the thin layer of relatively dry skin cracks very easily. If you have made too many, however, deep-fry them, and they will keep in room temperature for a couple of days. As a result, it is mostly sold fresh.

Tangyuan, on the other hand, freezes very well, which is why you can buy them ready-made from supermarkets. Ultimately, it is this difference between the two which led to the popularisation of tangyuan and not the yuanxiao.

(You can also keep extra filling frozen pre-rolling, but I just make tangyuan with those whilst I am at it.)

Cooking and Serving

Tangyuan is almost exclusively boiled. Yuanxiao, on the other hand, can be cooked in various ways, with the most common being deepfried and boiled. For a fair comparison however, I decided to boil both.

Bring a large pot of water to a rolling boil, then drop in the dumplings one-by-one. Stir occassionally to avoid them sticking to the pot or to each other. Once they float up, they are done! (Freshly made ones should take around 5 mins to cook, frozen ones will take slightly longer, but they do not need to be thawed before cooking.)

To serve, the most common soup bases are:

ginger and brown/rock sugar syrup, sometimes with Osmanthus

fermented glutinous rice wine 酒酿 (my fav)

For the first, you will need to smash large pieces of fresh ginger, add sugar to taste, and boil in water until the syrup in infused with the warm taste of ginger. For the latter, I just stir in a tablespoon of this in the plain dumpling soup.

TASTE TEST

Afterword

Thank you for reading!

Usually, I would just buy ready-made ones because it’s much easier, but I prefer the texture of yuanxiao filling, which is more interesting because of the combination of nuts.

Also, making yuanxiao is incredibly fun. And because there is no dough, it is actually quite simple and quick to make once you have your filling paste chilled. If you have extra filling paste left, you can just keep them frozen for next time.

This year, the Latern Festival falls on 26 February, which is THIS COMING FRIDAY (hence this post). So, friends, I encourage you all to give yuanxiao a go for a mini-weekend project :D

Appendix - Notes on Tangyuan

Both the Woks of Life and Chinese Sichuan Food (with video) have a very good recipes here and here on the dough and the method for this, and their filling also looks perfectly oozy. This video by Xiao Gao Jie is in Chinese, but recipe is available in English in the caption and I really recommend her technique.

All three methods pre-shape the filling into balls, I have done the same. Though not entirely traditional, it is more efficient.