Learning to Make Chinese Flaky Pastry

vs. Western style puff pastry, lamination techniques, and fat substitutions

Hi friends! This week I am sharing my experiences in making Chinese style flaky pastry.

The choice of title is deliberate because I am quite new to the foray of baking, and Chinese pastry is a very very deep rabbit hole of which I have just started to scratch the surface.

So why are you writing this? Three reasons: 1) it’s not very well known in the western world even amongst my foodie/baking friends; 2) there aren’t that many English resources around to introduce it to people; and 3) while reading up on recipes, I had questions that I couldn’t find answers to so I decided to do my own research.

As always, here is a mini ‘contents section’ of what I will cover, with Further Reading in Appendix:

What is Chinese flaky pastry?

Chinese flaky pastry vs. Western style puff pastry

Key techniques

Recipe

Fat Substitutions

Let’s goooo!

What is Chinese flaky pastry?

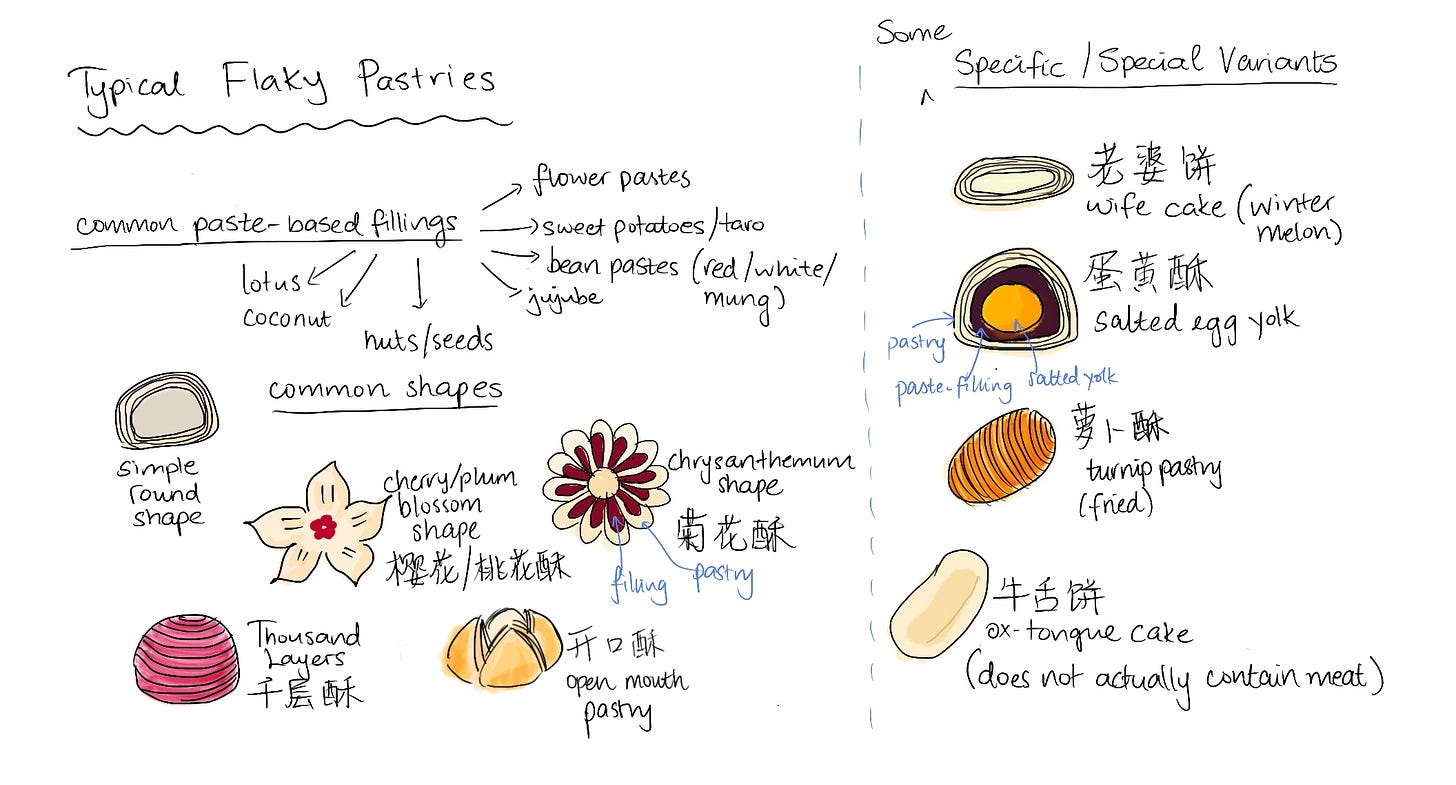

Like Western-style pastries, Chinese pastries also come in a variety of different doughs, with the flaky pastry being one of the most popular due to its versatility in flavours and shapes.

In case you are wondering where the pastry is used, below are some typical ones that you may have tried which uses flaky pastry as the base.

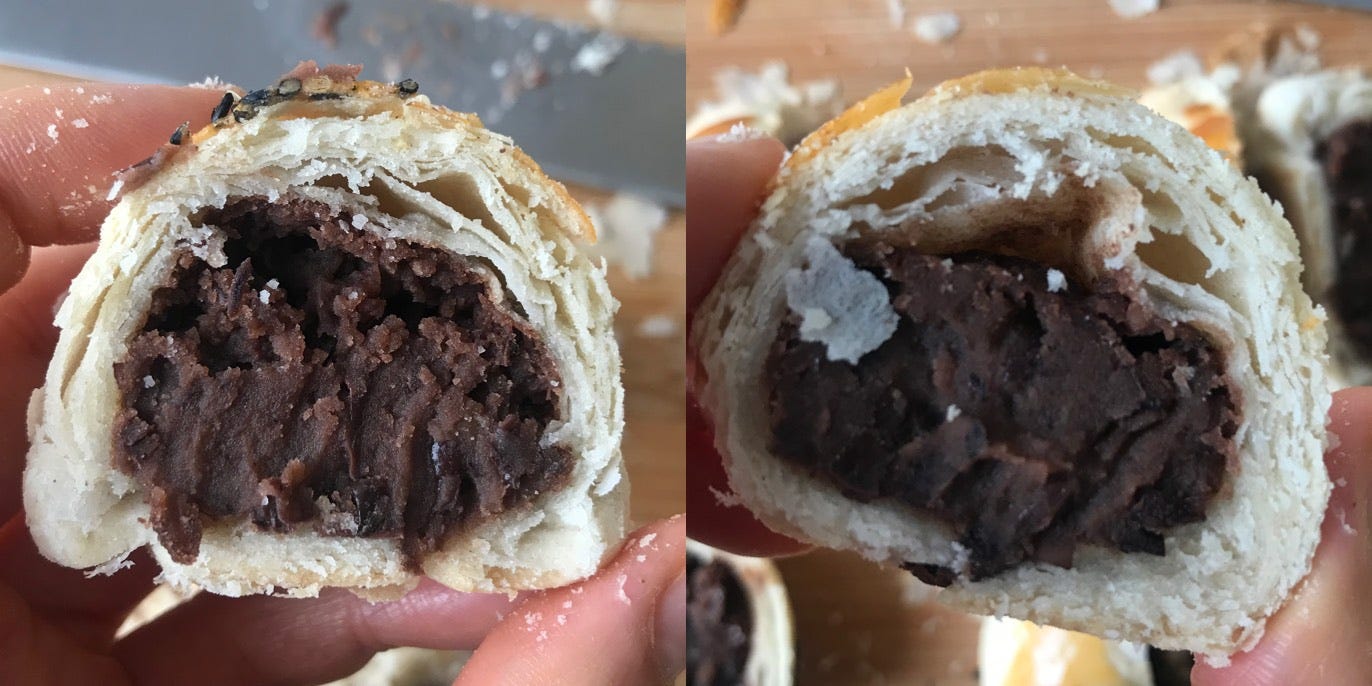

Strictly speaking, flaky patries also have different variants, the most common ones being ‘hidden’ 暗酥 and ‘visible’ 明酥. The former meaning the exterior is smooth and the layers can only be revealed once cut, while the latter ones have obvious layers visible from the outside.

Chinese Flaky Pastry vs. Puff Pastry: What’s the difference?

The layered effect and flakiness of Chinese flaky pastry resembles the western puff pastry; but they are ultimately quite different things.

Most noticeably, the flaky pastry is less rich and crispy and tend to be smaller in size, with round ones often the size of a plum, but might feel more dense per bite because of the paste filling.

Aesthetically, flaky pastries somewhat looks more humble: unglazed flaky pastries are as common as glazed ones, but can have a variety of colours. ‘Hidden’ pastries are popular, whereas most western desserts utilising puff pastry love to show off their beautiful layers.

The differences in appearance can be attributed to cultural aesthetic preferences: the rawness, simplicity, and modesty of unglazed hidden pastry has its own humble beauty, not to mention the ‘surprise’ you get when you take a bite and reveal the layers inside.

The taste and texture however, comes down to dough construction.

Here the most important difference is the choice of fat: lard — instead of butter — is the preferred fat in Chinese pastries. I will discuss its actual effect in the Fat Substitution section.

Compared to puff pastry, where an entire block of butter is encased within a water-butter-flour dough, the inner ‘block’ for flaky pastry is made out of a oily dough that is typically 2:1 flour:fat ratio.

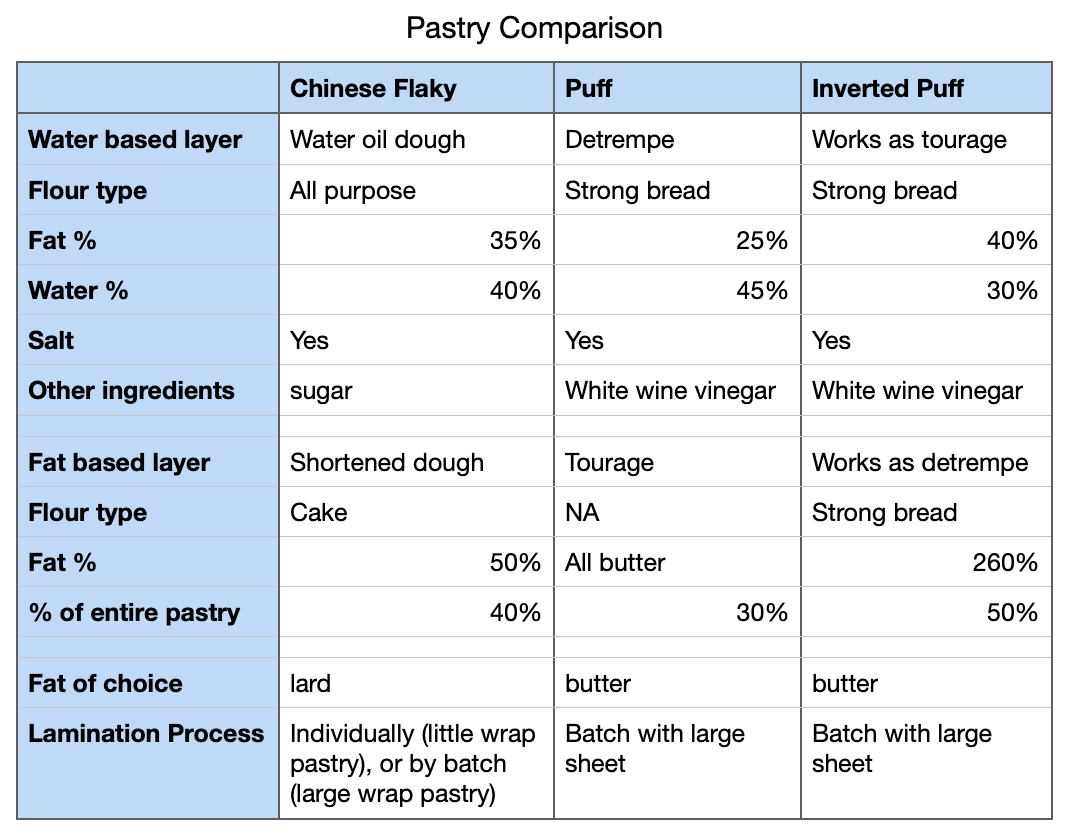

With my limited experience in making pastry at home, the chemical composition of flaky pastry dough seems to fall in between that of a puff and inverted puff. Comparison shown below.

In terms of dough handling, the encasing of the fat based layer into the water based layers is actually much easier with the flaky pastry, thanks to the high amount of flour in the shortened dough: NO FRIDGE NEEDED!*

However, this is also the reason why the flaky pastry ends up being less crispy than puff — there isn’t as much fat to ‘fry’ the dough when in the oven. Note here though, flaky pastries are also stovetop-friendly; you can pan-fry to cook or reheat them, whereas I am not sure you can do that with puff pastry…

(* if you live in the UK, except for 3 weeks in summer when it’s been getting too hot thanks to global warming…)

Key Techniques: Purlicue Enclosure and Individual Lamination

Let’s talk about techniques that might be new to you even if you have been baking lots at home :)

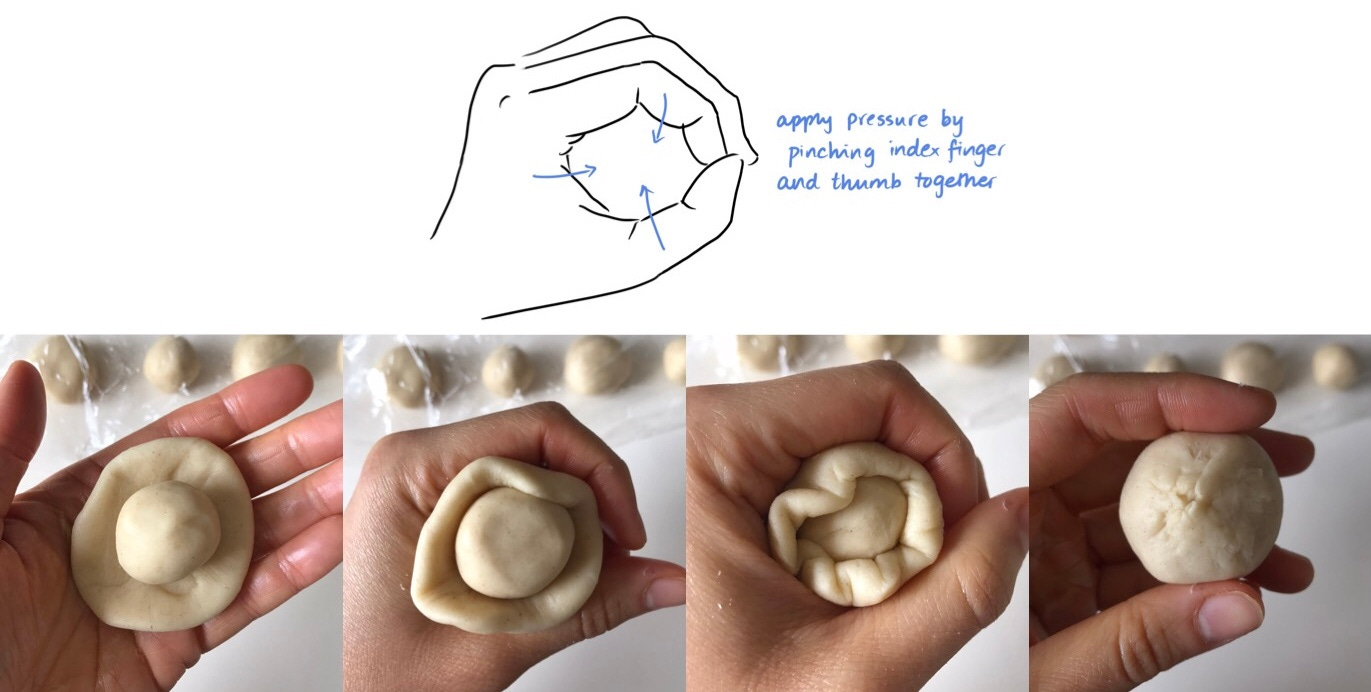

Purlicue Enclosure

This way of encasing round things is quite unique to Chinese pastries and is widely used not just for flaky pastries (including in wrapping mochi/glutinous rice dumplings).

In flaky pastries, this is used to encase the shortened dough into the water dough, and then again when encasing the filling into the final wrapper. For salted yolk pastries, you would also use this method to encase the egg yolk into the middle paste layer, before encasing that inside the wrapper.

This is how it works:

Don’t worry if you don’t want to do this though, rolling out an extra large outer dough, wrapping, then pinching off excess dough also works.

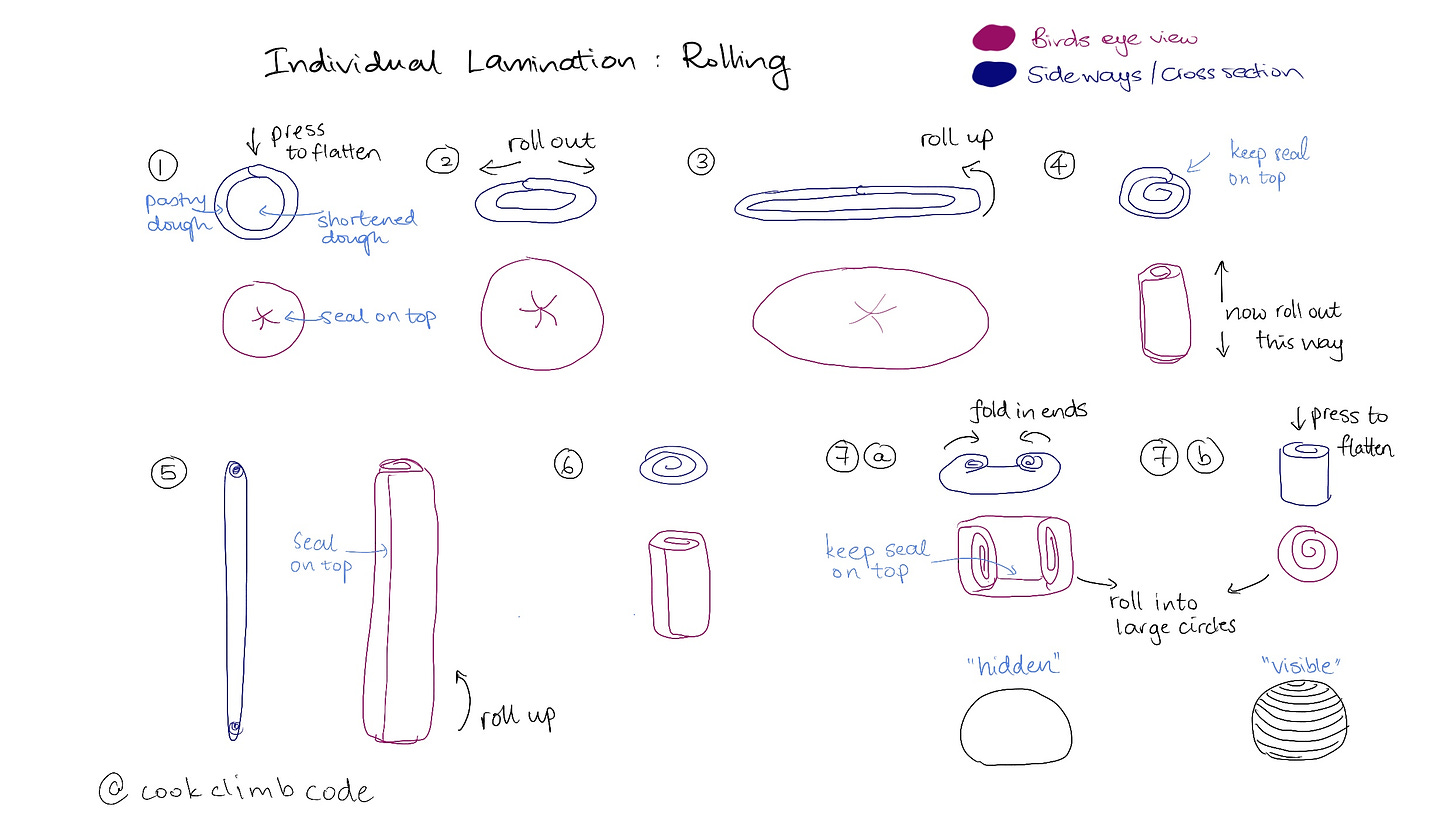

Individual Lamination

When making small batches (at home), individual lamination is the way to go. In addition, even in bakeries, using this technique will yield a more delicate pastry compared to the batch process with sheets and cutouts.

The first step is to have your shortened dough encased within your water dough as per the previous section.

There are 3 key points to note when doing the next steps:

ALWAYS have your seal on top (keep flat and smooth surface on the table)

Rest your dough after each roll to minimise tearing in the next stage

Use a press-and-roll motion when rolling out to maintain the layers

Traditionally, the lamination is done with a ‘rolling’ technique, steps best shown in diagrams as below:

But layers can also be formed with letter folds (fold twice), as you would with puff pastries.

Recipe

Ingredients (adapted from here) - makes 16

For the water dough:

150g All Purpose flour

53g lard, softened

60g water

15g sugar

a generous pinch of salt

For the shortened dough:

120g cake flour, AP is also fine

60g lard, softened

For a bean paste filling (brief method for this in appendix)

300g paste

Optional: 1 egg yolk to glaze; sprinkle of sesame seeds to decorate. You can add colour by subbing small amounts of flour in both doughs with e.g. cocoa or matcha powder.

Method

The method is best summarised at follows:

For kneading the water-dough: you will need to knead until the dough is smooth and has good gluten formation. Some recipes say that windowpane effect is required, this is not strictly true, but you want to ensure the dough is well formed to avoid the pastries tearing.

Resting: at least 30 minutes please. And keep your dough covered.

Shaping: Before lamination and assembly, you will need 20g water dough, 10-12g shortened dough, and 18-20g paste filling, all shaped into balls.

Then laminate and assemble as shown in the section above. To wrap your paste-ball, roll out your laminated wrappers, and use the purlicue method to seal.

Bake seal side down, at 180C fan for 25minutes, then 200C for 5 minutes for more colour.

Storage

Best consumed fresh but stores well at room temperature in a sealed container for at least 3 days. Reheat in oven at 180C for 5-10 minutes for best taste.

Fat Substitutions

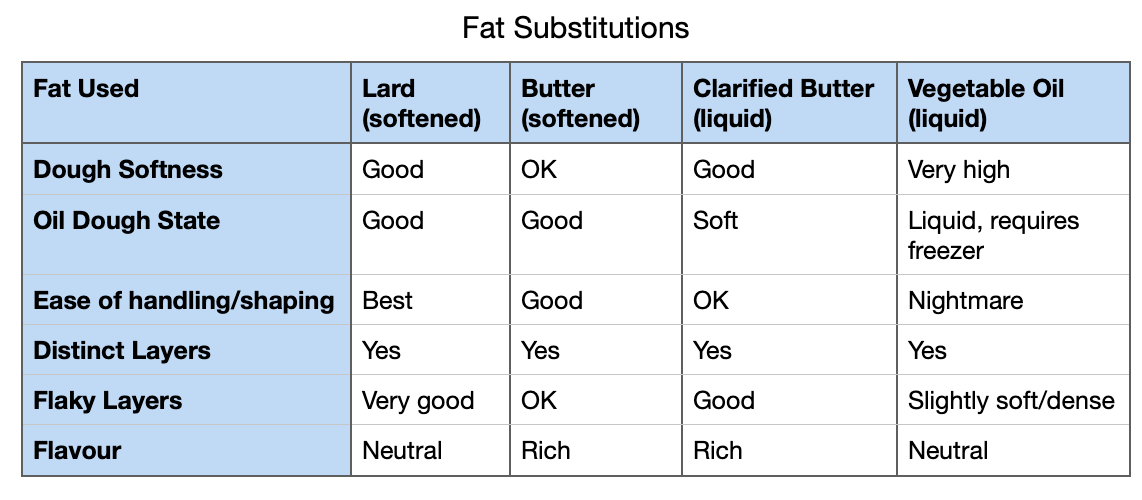

One of the most important aspects of the flaky pastry is the lard. It gives them a more neutral and humble flavour. Personal opinion: it is what makes them authentically Chinese.

But dietary requirements are common, and I read recipes that said other fats are ok too without showing the actual data. So I went ahead with my own experiments, all using the same recipe as above, but replacing the lard with other fats.

TL;DR: the recipe is relatively forgiving, all fats produced layers. For substitutions, butter is best for handling, clarified butter worked best for texture, but they did taste different. Liquid vegetable oil gave layers too, but was a nightmare to handle (I had to use my freezer) and yields a denser pastry.

Full details in the figures and captions below.

Afterword

That’s it, the end of the main post. Thanks again for reading!

This was certainly a super fun post to put together and I hope you have enjoyed this read.

There is more in the Appendix if you want to learn more, but in the meantime, please click <3 or leave a comment to let me know what you think, and share with any friends who you think might enjoy :)

As lockdown eases in England I hope to eat out a little more to support our friends in the hospitality industry, so in the short term I can’t promise long recipe experiments like this one. Instead, I want to share more thoughts on the cultural side and perhaps some general cooking/eating notes. As always, do let me know if there is anything in particular you want to see me write about.

Appendix

Notes on Home Made Bean Paste

For a standard can of beans in water (240g drained), be it haricot, butter, or adzuki beans, boil for 10-15 minutes to soften up. Drain the liquid. Optionally, remove the skins — I never bother. Mash the beans by hand for a rougher texture paste, or blend if you prefer smooth.

In a non-stick frying pan, add paste, and 2 tbsp of sugar, adjust to taste. On a gentle heat, evaporate the water. After 1 minute, add roughly 2-3 tbsp of oil — lard for more depth or use a neutral vegetable oil, keep on a gentle heat until it resembles the consistency of a thick tapenade or very thick custard.

Transfer into a container, then cover immediately with clingfilm. Let it cool.

Futher Reading

Regrettably there aren’t that many English resources, but:

Xiao Gao Jie video for Salted Egg Yolk Pastry (in Chinese but super useful for seeing the techniques including making bean paste in action, with English ingredients list)

The Woks of Life: Savoury Mooncakes Recipe

Notes on Huaiyang Pastry with diagrams on various styles of Chinese flaky pastry

your handwriting is so cute!! I think I will follow your recipe to make some this month :)